The debate

about The Charge of the Light Brigade of 25 October 1854 during The Crimean War

went on for over a century as academics, military men and others argued about

who to blame, Lord Raglan, the Commander, General Airey, Lord Lucan, Lord

Cardigan who commanded The Light Brigade, or Captain Nolan, the messenger.

There was a 1960's film, studded with stars and very costly, that gave a poplar

version, if free with the facts.

Had the shell

piece that struck down Captain Nolan felled the Earl of Cardigan all this may

not have happened. It is possible that the retreat may have been sounded but if

the debacle did occur, one to add to a long list, then a deceased Earl of

Cardigan no doubt would have borne the blame alone.

It is an

accident that I have had a look at this again. Trawling Census Returns of 1851

for Piccadilly for one thing, another caught my eye. It was a Mrs. Somerset who

gave her occupation as "Idleness". Entries of this kind are unusual,

especially among the aristocracy. But her husband, perhaps long suffering, was

Poulett Somerset a Captain in The Coldstream Guards.

A few clicks

later it was clear he was a grandson of a Duke of Beaufort, more to the point,

he was a nephew of Lord Raglan, a son of that Duke and was with Raglan as one

of his Aide's De Camp during the Crimean War. His wife was Barbara Augusta

Mytton, daughter of John Mytton of Shropshire; Mad Jack Mytton himself, the

noted hunter, horseman, rake and spendthrift bankrupt of The Regency Age.

This is a rich

mixture but the question in my mind is that when Raglan and Airey sent their

message to Lucan and Cardigan why did they not send Somerset, then a Colonel, a

man with the rank and the personal clout to deal with them rather than a junior

officer and of a lower order who they despised as a "professional"?

Nolan was a famous horseman but Somerset was also in the highest class.

Having been

with Generals when they were in discussion with staff officers when in the

field on war games I know what was in writing, but this was only a part of what

went on discussion of the options and issues. This applies to much of life as

we know it. What we do not know and cannot be certain about is who said what to

whom and to what effect?

So we cannot

be certain that when Russians were seen taking guns whether Somerset was in

favour of "doing something" and sending Nolan or doing nothing, in

that sending cavalry chasing off after a few lost guns when a major battle

might have been impending was unwise. As a huntsman he would have known that when

the chase is up once gone they are impossible to recall. Also, perhaps Raglan

needed him by his side.

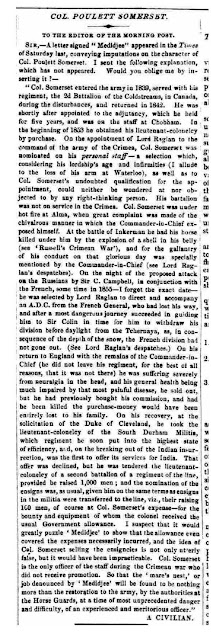

Later, in a

period when The Times newspaper was the gutter press of its day it was prone to

attacking people on the basis of tip offs from anyone with a pencil and access

to paper. One of their regulars called himself "Medidjee" and he had

a swipe at Somerset in 1858 but short on facts.

Below is a

response in The Morning Post of 10 March 1858 signed "A Civilian"

which apparently the Editor felt had to included on the front page. This

suggests it came from a very high placed source. This is a jpeg item which can

he increased in size.

Men of the

time had strong opinions which are strange to us and seem to defy explanation. We

should accept that what was logical and sensible to them may be difficult to

understand now and with hindsight we know to be wrong but that is the way of the

world. Somerset had clear ideas about what was best in cavalry training.

It was fox hunting as this piece from the

Leicester Journal of 27 February 1863 tells us on the occasion when he was

dined out of his spell in Gibraltar by the officers, again jpeg.

Also, a leading

author at the time George Whyte-Melville had been in The Coldstream's with

Somerset between 1846 and 1849. He was an avid hunting man and died in the

field when he fell off his horse and broke his neck.

To return to

The Charge, one thing that impressed it on the mind and opinions of the public

was the emotive poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the poet of the day written and

published very soon after the news broke in Britain.

He lived on

the Isle of Wight which might have seemed remote at that time but where Osborne

House was, the much loved country home of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Also, just along the road at Arreton on the Island was the aunt of one of the

prominent ladies of the court, one of a family with strong cavalry and military

connections and a sister of this aunt was personally connected to Colonel

Charles Grey, Private Secretary to Prince Albert.

There is more

to the row over where the blame might really lie for The Charge of The Light

Brigade than we know or ever can know. What we do know is that during the 19th Century as well as heroic victories and great achievements there were a good many

debacles and disasters.

And we need to learn from both.